One common misconception about Random Forest and overfitting

28 Mar 2021Introduction

Does 100% train accuracy indicate overfitting? There are numerous suggestions to tune the depth of trees in Random Forest to prevent that from happening: see here or here. This advice is misguided. The post explains why 100% train accuracy with Random Forest has nothing to do with overfitting.

The confusion stems from mixing overfitting as a phenomenon with its indicators. A simple definition of overfitting is when a model is no longer as accurate as we want it to be on data we care about. And we rarely care about training data. However, a perfect score on training data is usually a good indicator that we will face a disappointing drop in performance on new data. Usually, but not always. To understand why one should look at how Random Forest actually works.

To simplify, Random Forest consists of 1) fully grown trees, 2) built on bootstrapped data, 3) and the majority vote rule to make predictions. The first two concepts are succinctly explained by Leo Breiman and Adele Cutler themselves[1]:

“If the number of cases in the training set is N, sample N cases at random — but with replacement, from the original data. This sample will be the training set for growing the tree. Each tree is grown to the largest extent possible. There is no pruning.”

The third one is self-explanatory.

With these 3 concepts in mind, it is easy to see how Random Forest can produce 100% training accuracy. Consider a simple binary classification problem. If each tree is fully grown, that’s it — each leaf is a pure leaf, and each observation has a 62.5% chance to be sampled during bootstrapping, then more than half of all trees in the final ensemble ‘know’ the correct class for that particular observation. With the majority vote rule, that is enough to give 100% accuracy on the training set.

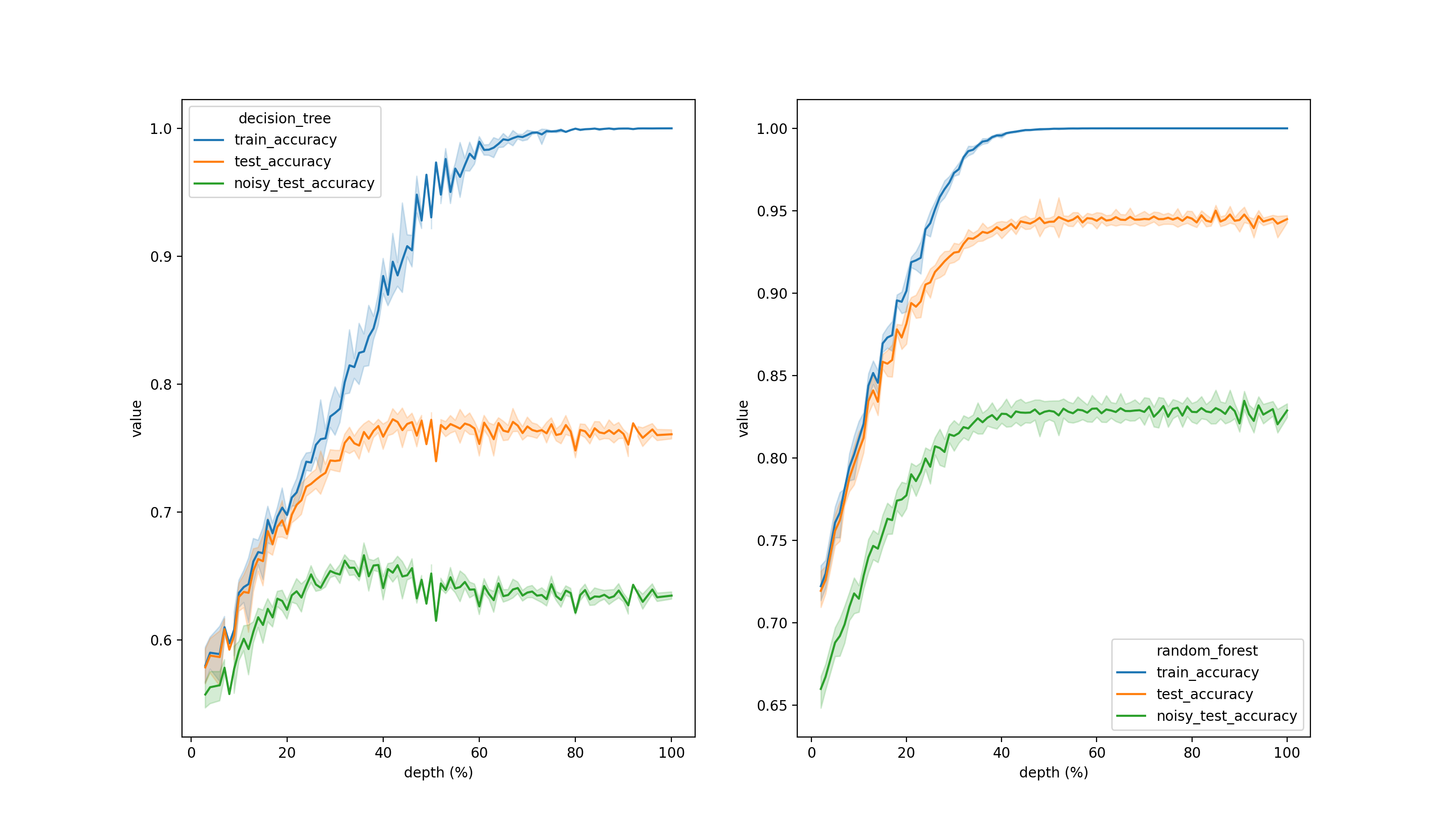

Let’s run a simple simulation. Define a binary classification problem and simulate some data accordingly. Then split the data into 2 parts: train and test. From the test part, simulate another test set by adding noise to some of the features. Train a fully grown simple decision tree and Random Forest on the train set and make predictions to the two test sets. Then, gradually reduce the depth and repeat the procedure.

As you can observe, deeper decision trees tend to overfit the data: accuracy on the test set with noise declines after ~35% of max possible depth is reached. Nothing like that happens to Random Forest.

Conclusion

- 100% accuracy on training data is not necessarily a problem

- Reducing maximum depth in Random Forest can save time. Excluding maximum depth from grid-search can save even more time

References

[1] L. Breiman and A. Cutler, Random Forests